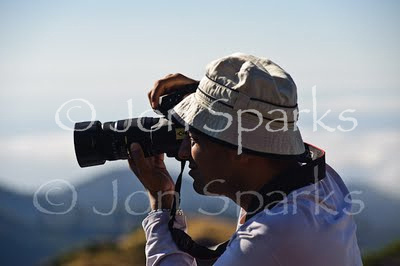

I’m sure many people never really think about this. The camera focuses automatically and that’s enough. However, as enthusiasts know, sometimes you want to focus on a subject and then just stay focused on that point. You may even want to focus on a subject and then hold focus while you reframe the image with that subject near the edge of the frame (i.e. outside the area covered by the focus points) – this is called focus lock.

Off centre-subject

At other times you want the camera to keep adjusting focus because you’re dealing with a moving subject; whether it’s moving across the frame, directly towards (or away from) you, or following some more complex trajectory, you want the camera to keep track of it and maintain focus on your chosen subject.

Single and Continuous

More sophisticated cameras, including DSLRs and the majority of mirrorless cameras, allow you to switch between single-shot and continuous autofocus modes. Single-shot modes work for static subjects – our first scenarios, a couple of paragraphs back. After all, if neither the subject nor the camera move, you only need to focus once. Continuous modes allow the camera to keep adjusting focus to deal with moving subjects.

Nikon (whose cameras I know best) badges these modes AF-S and SF-C respectively. That’s understandable; it probably becomes less clear when you see that the official full names of these modes are Single-servo AF and Continuous-servo AF. Hands up if ‘servo’ means anything at all to you...

Other camera-makers may use different jargon, but the basic single/continuous distinction still applies. For example, Canon’s equivalents (in most cameras, anyway) are One Shot AF, which is clear enough, and AI Servo AF, which is arguably even more obscure than Nikon’s terminology.

There’s also an auto option (AF-A, or AI-Focus in Canonspeak), in which the camera decides whether AF-S or AF-C should be employed. If it detects a moving subject it will use continuous AF to track it. However, I’m sure we can all imagine scenarios where there’s movement in the scene but the actual subject we want to capture is stationary. Or we may simply want to make our own decisions about when to use AF-S or AF-C.

‘There’s movement in the scene but the actual subject we want to capture is stationary.’

Normally, you switch between AF-S and AF-C using a separate control. On recent Nikon DSLRs, for instance, you hold the centre of the focus selector switch and turn the command dial (main command dial on cameras with two dials). It’s simpler than it sounds, but it takes practise to be able to do this without taking the camera from your eye, and it isn’t instant.

What if there was a way to switch from single to continuous AF at any time, with no delay, and without looking at any of the controls? Well, there is, and it’s called back-button AF.

Some cameras have a dedicated button on the rear which you can use for this. On Nikons it’s labelled AF-ON, but it’s only found on high-end models like the Df, D810 and D4s.

Separate AF-ON button on a Nikon Df

However, if like me you use something a bit more ordinary, do not despair. Almost every other Nikon DSLR has a button which you can set up to do the same job. It’s marked AE-L/AF-L. By default, if you hold down this button, both exposure and focus are locked, but you can change its function with a visit to the Custom Setting Menu. The only exceptions are the D3300 and its predecessors, which don’t have a Custom Setting Menu.

AE-L/AF-L button on a Nikon D750

Equivalent to the AE-L/AF-L button, marked with a star, on a Canon EOS 600D

With other models, you need to find the menu item called Assign AE-L/AF-L button, and change the setting there to AF-ON. Having done this, the other step you need to take is to make sure that autofocus is set to Continuous (AF-C). Do this once, and you’ll never need to change the AF mode again, because you’ll be able to shift between AF-S and AF-C at will.

Black magic?

This might sound like black magic, but it isn’t. Changing the function of the AE-L/AF-L button to AF-ON also stops the shutter-release button from activating autofocus. Now, only the AE-L/AF-L button can do this. And, because it has no other function, there’s no confusion. If you press it and then release when the camera focuses, focus then remains set at that distance – it functions as Single-servo AF and focus lock rolled into one. Press the button and keep it pressed, on the other hand, and Continuous AF remains active.

If you have a camera with an AF-ON button, you do have to ‘turn off’ the autofocus function of the shutter-release button; do this by changing the AF activation item in the Custom Setting Menu from Shutter/AF-ON to AF-ON only. Having done this, the AF-ON button then functions in the same way described for the AE-L/AF-L button in the previous paragraph.

No doubt this all sounds complicated. It did to me when I first started experimenting with back-button AF. But once I’d got used to using my right thumb to activate focus rather than my index finger, I soon realised things had actually become simpler. Not only can you switch between single and continuous AF at any instant, you also have no more worries about whether pressing the shutter-release button will cause the camera to refocus if you don’t want it to.

It took me a few hours to get used to it but soon it became second nature and now I wouldn’t have it any other way. I now set up this option on any camera that I’m using. Try it – give it a fair chance and you may find you never go back.

Mind you, it’s not entirely without pitfalls. It caused a little confusion last week when I lent my D600 to another photographer and next day he emailed to ask if knew that autofocus wasn’t working? I’d forgotten to tell him that pressing the shutter-release button wouldn’t actuate AF. Fortunately, that was quickly resolved. It’s something to remember if you share the camera with someone else – though that could be what User Settings are for. But that’s another story...

Back-button AF lets you jump from Single to Continuous AF instantly

]]>

A couple more credits: as second guide Tom brought along Jay Mulvey from MudTrek Mountain Bike Breaks, another excellent rider and good companion on the trails. And none of it would have been possible without our minibus and driver, Graham Draper of BikeBus Adventures (that’s a Facebook link as the website appears to be currently under reconstruction). Graham is also a skilled rider although it wasn’t possible for him to ride with us every day as drop-off and pick-up points were sometimes widely separated.

And thanks to the rest of the group too: Nik, Paul, Jeroen, Mark, Becky, Fiona and Anne. There was a range of skill and fitness levels but everyone was very supportive of each other. And as a photographer I was very glad that I could at least keep pace with most people – the whole essence of mountain bike photography is having to get ahead of people to shoot as they ride past, and then chase, catch up and do it all again.

On magazine assignments or commercial shoots, all the riders are effectively there as models and have a job to do. If the photographer needs them to ride a section of trail several times, or needs some people to hold flashguns while someone else rides, that’s part of the deal. They may help with carrying extra bits of kit, too.

In this case, however, seven people had paid to come on this trip as a holiday. That, and the fact that several of the days turned out to be pretty long anyway, meant that I needed, most of the time, to get my shots without disruption or delay to other riders. At most I might leave a snack/lunch stop a few moments ahead of the rest, or ask someone just to hang on a few seconds while I got sorted, but there was very little in the way of actually setting up shots or asking anyone to ‘do that bit again’.

Kit choices

With the foregoing in mind, I didn’t need to carry a vast amount of gear, and with some big days on the bike I was very glad not to have to. And I really don’t think I missed much by not having a fisheye lens or a 300mm. I’m a believer in keeping it simple anyway; I think when you look at the subject and the setting should speak for themselves. I’m turned off by images where the first impression you get is ‘oh, look, remote flash’ or ‘monster lens’.

I took two DSLRs with me, but only ever carried one at a time. I had my trusty Nikon D600 – perhaps not the most ‘pro-spec’ of Nikon’s FX (full-frame) cameras but nice and light, with a 24–85mm lens as standard. I also had a D7200, as I was in process of writing an Expanded Guide. This is currently Nikon’s top DX-format camera; I paired it with a Sigma 18–125mm lens. This doesn’t give quite such a wide view as the 24mm on the D600, but there’s over double the reach at the longer end. I also had a couple of extra lenses – a 14mm Sigma and 70–200mm f.4 NIkon. In the end I never toted the Nikon tele on a day out but I did take the 14mm with me a couple of times. Changing lenses is another thing that takes up time but in those majestic Scottish landscapes the wide-angle was really needed at times. I also had some remote flash kit which I used a couple of times.

To carry camera and any additional gizmos, as well as general riding kit, food, drink, etc, I used my LowePro Photo Sport 200 AW, which has a handy side-access compartment for the camera. See photo above (in this case with a Nikon D5300). This pack has been in the LowePro range for years – I’ve had mine at least six. ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’, would seem to apply here.

As to actual photography, one of the most important aspects of shooting in places you haven't been before is maintaining a kind of continual appraisal of the picture opportunities. This includes having eyes in the back of your head! Clearly on more technical sections of trail the focus has to narrow, but of course technical sections make for interesting riding shots so the appraisal still goes on even if it’s as a background process.

Anyway, here are just a few of my favourite shots from the trip, with brief thoughts on each.

Becky Nokes on the descent into Glen Tilt, Day 2

Nikon D600, 52mm, ISO 400, 1/400, f/5.6

There wasn't much sun to be seen on the first couple of days but on this long (near enough 50km) and remote ride I thought the misty conditions enhanced the epic feel. What caught my eye here was the way the trail pointed into the valley we were heading for. I stopped and let Becky go ahead and took several shots, but this one, where she's right at the intersection of the lines, stood out. I really like using tiny figures in big landscapes but the placement has to be just right.

Becky Nokes starting the descent to Achnashellach, Day 4

Nikon D600, 52mm, ISO 200, 1/500, f/5.6

This was, by general agreement, a superb descent. For me it was the best of the week and one of the best I’ve ever done – continually pushing the limits of the comfort zone without throwing up too many horrors. But this shot is more about the general feeling and atmosphere than any particular technical difficulty. In terms of photographic technicality, it’s pretty much nailed, with a wideish aperture for shallow depth of field so the background is slightly soft while the rider is pin-sharp. But I think what really makes it is Becky's complete focus on the trail ahead.

Jeroen Hoek on the descent from Bealach na Lice, Day 4; Beinn Damh behind

Nikon D600, 66mm, ISO 200, 1/320, f/11

This is an exception to the general rule that there were no set-up shots. While we were re-assembling the team and having a rest at the bealach, this superb light was calling to me and superfit Dutchman Jeroen was happy to ride down the first section of the descent and back up. It takes some processing in Lightroom to bring out the tones in such contrasty lighting and I may yet have another play with this image.

Paul Collins on the final descent to Torridon, Day 4; Beinn Alligin in the distance

Nikon D600, 46mm, ISO 200, 1/200, f/8

It’s getting well on into the evening here (about 6.30pm) and the descent isn’t done yet. This may not have been quite how Tom planned the day but it certainly played into my hands as far as photos were concerned. The light was just gorgeous. Paul’s green helmet certainly stood out in the shots!

Jeroen Hoek, Lochain Stratha Mhoir, Skye, Day 6

Nikon D7200, 20mm, ISO 200, 1/250, f/8

Our last day didn’t start particularly promisingly, with repeated pushes through peaty hollows breaking up any rhythm in the riding. When Jeroen decided to give his bike an impromptu wash, I saw the chance for a shot that would say something a bit different about the trip and about the nature of riding in wilder parts of Scotland. “This is not a trail centre,” as people said more than once.

Nik Wadge, above Kilmarie, Skye, Day 6

Nikon D7200, 24mm, ISO 200, 1/800, f/7.1

There isn’t anything particularly remarkable about this shot – nice background, fast shutter-speed to freeze the movement, and so on. One point I would make is that I got fairly low, sitting in the heather – a low viewpoint makes the rider more prominent as they appear against the sky. And it was very helpful of Nik to pop his front wheel up just here!

Nik Wadge, Anne Strafford, Mark Bale, Jay Mulvey, Fiona Vaughan, Jeroen Hoek,

descending to Camasunary, Skye, Day 6

Nikon D7200, 14mm, ISO 200, 1/500, f/8

This view, encompassing the entire Cuillin Ridge as well as Marsco on the far right, certainly wasn’t be missed. If I’d had the D600 as well as the 14mm lens, I might have been able to take it all in in a single shot, but that day I’d chosen to take the D7200 with its tighter crop factor. So I took several shots thinking I might be able to make a merged panorama later – and within a few days of getting home a new release of Lightroom gave me the chance to do that without even loading Photoshop. There are actually three frames in this merge, but all the riders were captured in a single shot.

Tom Hutton, Strath na Creitheach, Skye, Day 6; Bla Bheinn behind

Nikon D7200, 22mm, ISO 200, 1/320, f/6.3

I’m struck by the almost desert-like appearance of this shot – is it Utah maybe? No, it’s the Misty Isle of Skye in rainy Scotland. Technically the shot is straightforward, but I like the way that Tom’s helmet and riding kit match the colour of the sky, while everything else in shot is in a complementary palette.

Becky Nokes, Jeroen Hoek, Mark Bale, Gleann Sligachan, Skye, Day 6; Marsco behind

Nikon D7200, 18mm, ISO 100, 1/250, f/6.3

Just a couple of kilometres from the end, not just of the day but of an awesome week’s riding. I’m not sure why I dropped the ISO to 100 and could perhaps wish I hadn’t. The relatively slow shutter speed means that Becky, nearest the camera, is somewhat motion-blurred. Whether or not it spoils the shot is a matter of taste, I guess. I tend to prefer riders to be sharp unless I’m deliberately going for a panning shot or other impressionistic blur. This was another ‘set-up’ shot, as these three back-tracked and re-rode the visible section of trail while we waited for a couple of stragglers.

It's a nice camera in many ways and capable of excellent results, but in most respects not radically different from its predecessors. The headline feature on this camera is undoubtedly the introduction of a touch-screen.

This is the first time I've used a DSLR with a touch-screen but I’ve been working intensively with this one for a few weeks and I thought I’d share my initial thoughts about it.

I’ve always been somewhat sceptical about the benefits of touch-screens, at least on cameras which are fundamentally designed to be used at eye-level. Has the D5500 changed my views? Read on...

It’s worth saying at the outset that when I’m working on an Expanded Guide I do all sorts of things with a camera that I generally wouldn’t do in my regular shooting. This is obviously necessary in order to be properly familiar with all the modes and functions. And it isn’t a bad thing for me personally as it does mean that I don’t get totally set in my ways. I do regularly get a fresh perspective on my habitual ways of working and this does occasionally lead to changing the way I do things.

It’s worth saying at the outset that when I’m working on an Expanded Guide I do all sorts of things with a camera that I generally wouldn’t do in my regular shooting. This is obviously necessary in order to be properly familiar with all the modes and functions. And it isn’t a bad thing for me personally as it does mean that I don’t get totally set in my ways. I do regularly get a fresh perspective on my habitual ways of working and this does occasionally lead to changing the way I do things.

A quick example: I was pretty sceptical about Live View when it first appeared. A DSLR is an eye-level camera, isn’t it? Well, it is, and the viewfinder will always be my first choice for most shooting, but Live View does have an advantage when focusing is super-critical, e.g. shooting with very long lenses or in macro. It’s very accurate and you can zoom in on any part of the image to check focusing even more precisely. My default setting for macro shooting is now tripod + Live View zoom + manual focus. I’d probably have figured that out sooner or later but because working on the Guides obliged me to explore Live View, it happened sooner.

But back to the touch-screen. Let’s look at how it works in four main areas: normal shooting (i.e. using the viewfinder); Live View (and movies); menu navigation; and playback.

Normal shooting

Normal shooting

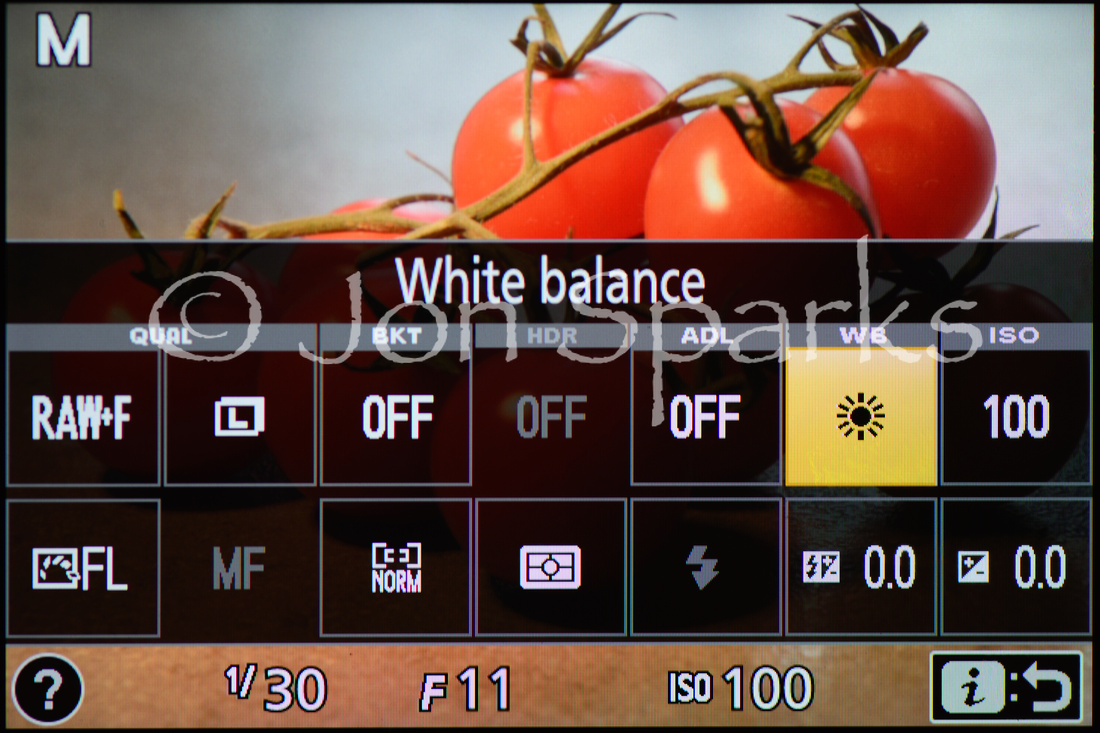

Again, working on a Guide is not like my regular everyday photography. It involves a lot of playing around with different modes and different settings. And for a lot of this, using the touchscreen probably is significantly quicker than using more traditional methods. For many operations on the D5500 you have to highlight a setting using the multi-selector (most other cameras have an equivalent control), then press OK to activate it. With the touchscreen a simple tap turns two steps into one. Not only is this quicker, this soon feels intuitive too.

However, some of these comparisons would pan out differently on other cameras which have a few more dedicated buttons. In fact, all the SLRs ‘above’ the D5500 in the Nikon range also have a separate control panel on the top-plate and it’s easy to change key settings like image quality, white balance and so on using this: just hold the appropriate button and turn the main command dial (or sometimes the sub-command dial for further options). This is quicker than activating the touchscreen and then making a change in settings – but only once you’re familiar with the location of the buttons. I can see that many photographers new to DSLRs – especially if they’re familiar with other touch devices like a smartphone or tablet – will now never learn where the buttons are, and so will miss out on what can be the quickest way to change many settings.

I also am fairly sure, though I don’t have hard evidence, that using the control panel is less draining on the battery than using the touchscreen. This is probably of no practical significance unless you (a) change settings an awful lot and (b) are on a long trip without a spare battery or chance to recharge. But still...

There’s one area where the touchscreen is clearly much slower – and it’s a pretty basic one. This is in setting aperture or shutter speed. First you have to activate the display then tap on-screen arrows – and each tap only changes the setting by 1/3 Ev. It’s far quicker to use the command dial. On the D5500, which only has one command dial, you have to hold the exposure compensation button and turn the dial to set aperture in manual mode, but it’s still loads quicker.

What's more, you can change shutter speed and aperture without taking the camera from your eye as they are shown in the viewfinder. This is particularly important if you’re shooting sports or other action. And the same applies to ISO setting, too, which of course is the third point of the ‘exposure triangle’ and really, on a digital camera, should come into play just as much as the other two. On the D5500, you hold the Fn button (assuming you haven’t changed its default function) and turn the dial to do this. You do need to change a Custom setting (b2, since you asked) to get ISO shown in the finder, but this is a one-time action and honestly it’s a no-brainer. Do it.

In my everyday shooting, I’ll probably never touch most of the settings (Image quality, Picture Control, White Balance, etc) from one end of the day to the other. The things that I do adjust all the time are shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. The touch-screen is a hindrance for these, so I’ll make little or no use of it in normal shooting.

Live View

Live View

In Live View, of course, things are a bit different. The screen is already active and you’re using it to frame shots anyway, so there’s much less time lost in transferring your attention to the touch-screen. For most settings, especially the ones you can access quickly by pressing the i button (see footnote), it’s probably quicker to use the touch-screen. It’s still way quicker to use the dial for shutter-speed and aperture, however, and it’s probably a score-draw when it comes to ISO.

But the touch-screen does bring something new to Live View; the ability to tap a point on screen to make the camera focus there. This is much, much quicker than laboriously moving the focus point with the multi-selector and then pressing another button to make the camera focus on it. A big win for the touch-screen here, I’d say.

However, I should add that this only speeds up your half of the focusing process – the bit where you tell the camera where to focus. Actual focusing (the camera’s part of the process) in Live View is still a bit slow and certainly not much good for shooting action. (Surprising that Nikon’s DSLRs aren’t better at this, when the focusing in the Nikon 1 mirrorless cameras is so good).

Personally, when I’m using Live View, I’m also using manual focus much of the time. And what would speed this up is if I could zoom in on the key area with a gesture, or even press the zoom button and then drag a finger to see a different area in the magnified view. Without this, zooming to view a particular area means you have to position the focus point over it first and then use the zoom button. It’s a let-down, and doubly so because you can gesture-zoom in playback (see below).

There’s one other aspect that I haven’t mentioned, which is the ‘touch-shutter’. You have to enable this by tapping an icon on the screen. Once you’ve done this, if you tap a point on the screen the camera will focus there – and when you lift your finger it will take a shot.

I’m really not convinced there’s any advantage to this. Yes, if you’re interacting with the camera solely through the screen, it may seem logical to have this option. But every time you focus on A and then decide you don’t want to take that shot and want to focus on B instead, the camera will take a picture anyway. Of course you can delete the unwanted shot(s) afterwards but still, a function that takes pictures you don’t want is not a very smart function. Needless to say, I quickly disabled the touch shutter and don’t envisage ever using it again.

Menu navigation

Menu navigation

On the face of it, the touch-screen speeds up menu navigation enormously. Instead of scrolling to an item to highlight it, and then pressing OK to accept or move to the next step, you can just tap the item. It cuts the time taken by at least 50% and often much more.

However, the downside for me is that every now and then I tap on the wrong item. You do need to be quite precise as the target areas are quite small (just over 4mm deep). Or maybe it’s just my clumsy fat fingers. And when you do tap in the wrong place it often means having to undo the setting you didn’t mean to change before going back and redoing the one you did.

Still, on balance, it’s a notable improvement. And in one area – text entry – it’s absolutely streets ahead of the older way. I might even use features like Image comment more often now that entering text has become easy, instead of painfully tedious.

Playback

Playback

On the whole I think playback is where the touch-screen really shines. It is natural and easy to swipe left or right to scroll through pictures, and to stretch or pinch to zoom in or out. The improvement is even more noticeable when you hand the camera to someone else who wants to look through your pictures; they’re far more likely to be used to this way of doing things than using the multi-selector.

There’s one blemish, though. You can scroll left or right by touch but you can’t scroll up/down through the different info screens for each image (highlights, histogram, metadata and so on). I use these a lot, especially the histogram, which any serious photographer should refer to regularly. You still have to use the multi-selector for this, and it feels more awkward to do so when you’re switching to it from intuitive gesture-navigation. If Nikon can fix this for future iterations it will be a real benefit.

In general

Of course some of these comments are determined by the specific way Nikon has implemented the touch-screen on the D5500 and some of the shortcomings I’ve mentioned could easily be addressed. Even so, there are clearly some areas where using the touch-screen is easier and faster than other methods and as long as I’m using the D5500 (though it’ll be going back in a few weeks), I’ll happily make use of them, probably more so in Live View than in normal shooting. Nikon’s implementation for Live View does leave a little to be desired, but it undoubtedly speeds up certain operations.

At the same time, I do still have a few reservations. The first is one I’ve already mentioned – that photographers new to DSLRs may get suckered into using the touch-screen for everything, even those areas where it clearly isn’t superior. An SLR is still first and foremost an eye-level camera. You should be able easily to adjust crucial settings without taking the camera away from your eye – and you can.

I also wonder about the durability of the touch-screen, which of course now gets much more hammer than non-touch-enabled screens. After the first day or two playing with the camera, the screen was already seriously in need of cleaning. Nikon doesn’t provide any sort of screen protector but if I were going to keep this camera I’d certainly be looking for one. And as an outdoor photographer, sometimes shooting under time pressure in challenging conditions, I’m a bit concerned about the ruggedness of fold-out screens more generally, too.

As an outdoor photographer I’m also very conscious of how cameras handle when you’re wearing gloves, and clearly touch-screens and gloves don’t play nicely together. (I’m aware there are gloves which claim to work with touch screens but you still lose some of the precision which is definitely needed to use this one). Clearly I’m not going to be pulling off my right glove every time I want to adjust something, so it is important that control through buttons and dials remains available and straightforward. Any camera that only lets you do things through a touch screen is a non-starter for me (one reason why I don’t see the iPhone as a serious full-time camera).

Bottom line

I guess I half-expected to find that a touch-screen on a DSLR was a pointless gimmick. It’s not. It’s genuinely useful and beneficial for some things. But it’s not a panacea and some operations are still best done by other means.

In future if I have a camera with a touch-screen in my hands I’ll use it for the tasks it’s good at. But the presence or absence of a touch-screen is going to be fairly low on my list of priorities next time I go looking to buy a camera for myself. I like it more than I expected to but I can still live without it.

Footnote: Settings you can access quickly in Live View by pressing the i button:

Image quality, Image size, Bracketing, HDR, Active D-Lighting, White balance, ISO, Set Picture Control, AF mode, AF-area mode, Metering pattern, Flash mode, Flash compensation, Exposure compensation

Out of these, ISO, Flash compensation, and Exposure compensation are more easily accessed by button and dial.

I think Metering pattern is a waste of space here. I never shift out of matrix in normal shooting: for critical exposure assessment I rely on a test shot and looking at the histogram. I’d like to bet that upwards of 95% of owners of a camera like this will use matrix all the time too, or depart from it once in a blue moon. I’d far rather see Release mode on this list. There is a dedicated Release mode button on the D5500, but it’s in a rotten place – a rare fail for Nikon, who usually do a damn good job with their camera ergonomics.

]]>The person responsible for the image in question proclaimed that whether I like it or not is irrelevant to him – though this, of course, begs the question of why he bothered to respond at all. He then referred to my ‘cursory dismissal’ of his image. He also used the word ‘art’ in reference to his own work, but let’s not even go there.

I might have been inclined (and might have been wiser) to leave it at that point but the phrase ‘cursory dismissal’ got my back up. My response wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment thing and I can prove it – as we’ll shortly see.

I also observed with interest that some people had commented approvingly on the image without, apparently, realising that it was not a straight photograph. You’ll have noticed that I have not referred to the picture in question as a photograph but only as an image. The originator did (though only after being called out) admit that it was a composite of two photos.

Now I don’t have his permission to reproduce it here, and I’m not asking for it, as I don’t want this to become any more personal than it already has. I did, at the start, say I hated ‘this sort of thing’, rather than his photo specifically.

So what ‘sort of thing’ are we talking about anyway? Well, the image in question showed a field of flowers (oilseed rape I think) and a tree, under a deep red sky. There’s no doubt in my mind that the colour of the sky owed much to either a red graduated filter at time of shooting or to some heavy post-processing. If the sky had been that red in reality there would surely have been a distinct shift in the colour of the flowers too.

So already we have an image that has been altered well beyond what would actually have been visible at the time of shooting. But that’s not all. Floating in that red sky was a huge full moon.

Now to me it was instantly obvious that this image could never have been created as a straight photograph. There are at least two reasons why it’s impossible; I’ll explain more fully shortly. But let me just go back to that glib accusation of ‘cursory dismissal’. This is not the first time I’ve seen this kind of image. In fact I wrote something about it as far back as 2002, in which I specifically referred to ‘impossible shots created by double exposure, like a telephoto moon hovering over a wide-angle landscape.’ To which I added, ‘These make me almost queasy.’ 13 years later, they still do. (That original piece is reproduced at the end of this blog post).

Of course, that is a personal reaction, and if other people like this sort of thing, that’s fine. At least up to a point... I do genuinely think, after considerable reflection, that there are reasons to be, at least, very wary about this sort of thing. Most of all, we do need to be very clear about what is or isn’t a constructed fantasy image.

Anyway, as I’ve already mentioned, it struck me that some people didn’t seem to realise that the image was a fantasy and that it was both optically and astronomically impossible for it to be a straight photo. So let’s just dissect this a bit.

Here’s an example. I know it’s very rough and not in any sense convincing. To do a better job I’d need a clearer image of the moon and I’d need to do a much better job of masking around the branches of the tree. But I’m not interested in spending that much time on what would still be a counterfeit image. All I need this image to do is illustrate the two main reasons why nothing like this could ever be seen with the human eye, or captured in a single photograph.

First reason: the moon is too big.

First reason: the moon is too big.

Second reason; the moon is in an impossible place.

Just to help explain all this, here are the two original images, un-meddled with.This image was shot on Farleton Fell in Cumbria, a favourite spot of mine, late in the afternoon of 23 November 2007, using a Nikon D2x. The focal length was 18mm – equivalent to 27mm on 35mm/full-frame: in other words, a moderate wide-angle lens.

The moon image was shot about 20 minutes later, and not very far away, so in one sense the two shots are related. However, there are two crucial differences.

The moon image was shot about 20 minutes later, and not very far away, so in one sense the two shots are related. However, there are two crucial differences.

First, it’s taken with a 300mm lens (450mm equivalent). This means that the moon appears almost 17 times larger than it would if I’d shot it with the same focal length as the previous. Second, for this shot I’m looking in a completely different direction.

First, it’s taken with a 300mm lens (450mm equivalent). This means that the moon appears almost 17 times larger than it would if I’d shot it with the same focal length as the previous. Second, for this shot I’m looking in a completely different direction.

Size

As far as the size of the moon is concerned, placing an oversize, telephoto, moon into a wide-angle landscape plays havoc with normal perspective. Perspective is a vital element of how we judge scale and distance and make sense of the world. It’s been well understood by scientists and artists at least since the Renaissance, and I would have thought that an intuitive grasp of perspective is established in most people at a very early age.

Of course artists like Escher have played very deliberately with perspective to create visions of impossible structures. There’s nothing wrong with that. And there’s nothing wrong with fantasy images as such – but even fantasy needs some level of internal consistency.

In fact the moon was once much closer to earth, and it’s still drawing slowly further away at a rate of about 3.8cm a year. This has been measured with great precision, as the Apollo astronauts placed reflectors on the lunar surface and scientists can bounce laser beams off these to determine the distance.

Therefore there was a stage in the very distant past when the moon did look as large as this, though there were no humans around to observe it (let alone cameras) and both moon and earth would then have looked very different. Tidal forces were much more extreme and the length of a day on earth was much shorter.

It is possible to imagine a world with either a much larger moon than our own, or a similar sized one that’s much closer. In fact, to appear as large as this while remaining at the same distance as our own moon is today, the ‘moon’ would have to be around four times the Earth’s diameter. It would be the planet and Earth would be the satellite. But four times the diameter implies 64 times the volume, so even if the planet were much less dense than our own Earth or moon, it would be much more massive. The implications go on and on...

Direction

The second reason why the image is impossible is that it places a full moon in roughly the same direction as the (in this case) setting sun. It doesn't matter whether it’s sunset or sunrise as the full moon will always appear in the opposite direction to the sun. You can easily verify this for yourself. A full moon will rise in the east in the late afternoon or early evening, when the sun is sinking in the west. For sunrise/moonset, the same applies but the directions are reversed – sun east, moon west. The reason for this is very simple; the moon is lit by the sun. When the moon is between us and the sun, the side facing us is in shadow – we call this a new moon. (And on the rare occasions when they line up exactly, we get an eclipse).

The only way that you could see a fully illuminated moon in the same part of the sky as a rising or setting sun would be if we were on a planet in a binary star system. In other words, there would need to be two suns. And even then, if there were such a big and bright moon, wouldn’t it dilute the red glow of the setting second sun? And wouldn’t a moon as bright as that cast shadows of its own?

I hope I’ve done enough to show that images like this are impossible. That is to say, nothing like this will ever be seen on Earth by the naked eye, nor can it ever be captured in a single exposure by any camera. But does it matter?

Well, if such images are clearly recognised as fantasy constructs, maybe not. I enjoy fantasy and I could enjoy the vision of a world with a huge moon, or imagine living in a binary system. But, as I said earlier, even fantasy needs some level of internal consistency. And a 17-times-too-big moon in the skies over a normal landscape raises all sorts of unanswered questions – never mind the second issue of ‘what’s making it shine?’.

Some people may be able to view such images without asking such questions but I can’t, and I think failing to grasp what’s ‘wrong’ with such images implies a lack of understanding of some fairly basic facts about the world.

Still, most of us would probably say that there’s no harm in fantasy as long as we all know that it’s fantasy. My worry is that if we aren’t clear about the nature of constructed images, we devalue genuine photography. If we can’t tell what’s real and what isn’t, where’s the sense of wonder in a real photo of the Milky Way or the Aurora?

After The Two Towers:

Fantasy, Reality and Photography

This was originally written at the end of 2002 and appeared in a long-gone online magazine. I’m repeating it exactly as written, complete with references to other articles that I can’t now trace. At this point I hadn’t acquired my first digital camera (that was in 2004) and was still shooting slide film.

The Two Towers, the second part of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, is currently packing ‘em in at cinemas across the country. Don’t miss it: it’s probably the greatest fantasy movie ever made. It’s also worth seeing simply to admire the seamless blend of conventional film and digital images. The character Gollum is a brilliant creation, but there are also many amazing partly or wholly digital landscapes.

As a fantasy film, pure and simple, it’s a masterpiece. However, we also know that the real footage was shot on location in New Zealand. New Zealand is now Lord of the Rings country, and frenetically selling itself as such. Well, on one level, good luck to it. But there is a problem. The New Zealand Tourist Authority would no doubt like us to think that the landscape we see on the big screen is what we’ll see when we go there. But how, with so much digital content, can we be sure? How, indeed, can we be sure of anything we see?

This has been most discussed in relation to news and documentary images, but it concerns all photographers. The Nature Group of the RPS, for example, in its Nature Photographer’s Code of Practice, states that: ‘a nature photograph should convey the essential truth of what the photographer saw at the time it was taken’. A similar stipulation is built into the rules of the BG Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition.

As a landscape and travel photographer, I have been concerned with these issues for some years. The Two Towers just kept the pot simmering. What really stirred it up was the January issue of In Focus, with the fortunate, if not fortuitous, juxtaposition of two fascinating articles: Niall Benvie’s Seeking Ecological Asylum and Mike Busselle’s Decisions. If you haven’t already read them, one of the beauties of a webzine is that you can do so now. But to summarise, Benvie’s article is a powerful meditation on our relationship with nature and landscape, and what it means to us as photographers. Busselle’s explores some of the possibilities offered by digital imaging.

I’m not a digital Luddite. I’m not concerned whether an image is initially captured on silver halide crystals or on a CCD. Nor do I have a blanket aversion to ‘manipulation’. Mike Busselle’s first two examples illustrate a powerful argument in favour of digital capture: the potential to control local tonal values more subtly and more precisely than would ever be possible with a filter. As Mike says, ‘I’ve always considered the neutral graduate to be one of the most useful filters but, in truth, it offers a fairly crude and limited degree of control...’ And these aren’t the only limitations, as I’m well aware, having recently had a neutral grad snatched from my hands by a strong wind on Helvellyn!

So I’m happy to embrace digital technology, whether in initial capture or later manipulation, as a way of fine-tuning the image: improving shadow detail, removing unwanted colour casts, and of course getting rid of dust and scratches. However, when manipulation alters the actual content of the image, it’s a different matter. I would argue that, just like a nature photograph, ‘a landscape or travel photograph should convey the essential truth of what the photographer saw at the time it was taken’. In the context of a fantasy like The Two Towers the only limit is the human imagination. But in, say, a New Zealand tourist brochure, an image should be - at the very least - a reasonable guide to what one could expect to see at that location.

This conviction has developed during my own career. Over ten years ago, when digital technology was a lot less familiar, I was commissioned to photograph a local church which, for historical reasons, flies the Stars and Stripes on July 4th each year. On the day the light was good and there were no parked cars in the way, but there wasn’t quite enough wind. Lancaster Tourism asked me if they could blend in a flag shot by another photographer, and I agreed. I hadn’t anticipated that they would tell everyone about this when they launched the resulting greetings card.

This image isn’t really misleading: you might see it just like this on another July 4th. Still, it returned to haunt me a few years later. After some detective work I’d found a spot where I could get a view of Lancaster Castle with the Lakeland fells behind. A ‘window’ in the trees framed the shot perfectly.

This has become my most reproduced shot, appearing on greetings cards, posters, calendars and in magazines and tourist brochures. It has also attracted much comment locally, because most people weren’t familiar with this view. Many have asked me how it was done: some have simply branded it a ‘fake’ - citing the Stars and Stripes image as evidence that I manipulate images.

Having been quietly proud of how I’d found the viewpoint, these comments stung. It felt like an attack on the truth of the image - and, by implication on my own honesty. And it led to a decision. I started putting the following on invoices and delivery notes: Substantive manipulation of these images is not permitted, except in special circumstances and by prior agreement.

What I mean by ‘substantive manipulation’ of an image is simply anything that changes the substance: taking out something that was there or adding in something that wasn’t. Tweaking the contrast or colour of an image is a matter of interpretation, at least up to a point,: colouring the Taj Mahal bright green would surely be a substantive change!

When you make changes like this, or allow someone else to do so, you are no longer just interpreting the scene, you are materially altering it. And when that image is presented, explicitly or implicitly, as a representation of a real place, it becomes a falsehood. Which, if you are in the business of travel or landscape photography, is a serious matter.

Of course parked cars and power-lines can be an irritating distraction. Cars come and go, and sometimes you can ‘lose’ a power-line just by choosing a different viewpoint. But if you can never see a scene without parked cars, that’s the reality. (Maybe the answer is to campaign for more yellow lines.) If there’s no way to see the view without power lines, that too is the reality.

These issues are not new. Manipulation is as old as photography itself. Combination printing, air-brushing and retouching, double-exposures and slide sandwiching have all been used. We’ve all seen impossible shots created by double exposure, like a telephoto moon hovering over a wide-angle landscape. (These make me almost queasy). What is alarming about the digital aspect is the utterly casual way in which images are manipulated without a second thought. But a falsehood is a falsehood, whether or not it’s created digitally. And I think it’s wrong to tell lies.

My resolve on this point was tested again more recently, when a book publisher wanted to ‘remove’ a rock from a potential cover image. However, having declared in the book that none of the images had been manipulated, I really had to stick to my guns. Fortunately we were able to agree on an alternative shot.

What’s the harm? Was that rock really important? Maybe not: I could easily have taken a shot without it, just by moving along the beach a few metres. But as the sun came up on that particular morning, that was the shot I felt I wanted to take.

I can’t say that removing the rock would significantly mislead anyone about the location. But it would mean that the image was no longer the shot that I took. It would no longer be the embodiment of what I saw and what I felt.

What this illustrates is that there’s another side to this debate: it is not solely a simple question of honesty. It also has something to do with what it means to be a photographer. For me, it comes back to why I became a photographer in the first place, why photography still excites me9, why it will never be just a job.

For me, being a photographer is about being there. It’s about the whole experience of a place and the effort to capture an image that says this is what it was like. It’s why the time spent walking around, looking, touching, listening, even smelling, are as important as time spent looking through the viewfinder. And ultimately, photography is about those moments when everything comes together: when the light and the weather conspire to make magic.

Moments. Decisive Moments. ‘Being there’ is not only about place; is is also about time. In the studio you may be able to repeat a shot exactly. In the natural world every moment is unique. Clouds move, the light shifts. Over longer time-scales, streams alter their courses; trees grow and fall. So do mountains, if you wait long enough.

‘It may seem paradoxical that a still photograph can capture this dynamism - but there’s no doubt that it can, just as it can capture the dynamism of an athlete or gymnast. And the process of landscape photography - the actual doing of it - means tuning in to the dynamism of land, light and weather. It means developing a relationship with the landscape - which is, at least partly, what Niall Benvie discussed last month. It doesn't make it easy, but it does make it endlessly rewarding.

I’m more than happy with anything that helps me to express what I saw and felt. Some forms of manipulation - be they filters, traditional darkroom techniques or Photoshop’s Curves dialog - can help to sharpen that sense of being there. But deleting a rock, or importing a ‘better’ sky from another time or place, destroys it. It negates everything that makes me want to be a landscape photographer.

The problem with manipulation, then, is not just about the literal truth of an image or whether it creates a false picture of reality - though this is in itself a very serious issue. It is also about something of more personal concern to all of us: it is about what it means to be a photographer.

]]>This has irritated lots of professionals, like me. I’ve licensed images to OS for map covers in the past and been paid for it. You can hardly expect pros to be thrilled when yet another once paying client decides to try and get all the images it needs for free.

However, if you’re an amateur photographer, you might think this isn’t your problem. Seeing your photo on the cover of an OS map sounds quite exciting, doesn’t it? What’s more, if your photo is one of the ones selected, you get a free copy of the map in question and a year's subscription to OS Getamap. The overall winner gets £750 of holiday vouchers and the junior winner gets an iPad mini. And if you don’t win, well, what have you got to lose?

Well, potentially quite a bit, but maybe not so much as you would have if people like me hadn’t kicked up a stink. Overnight, and without much fanfare, they have changed the terms of the competition.

Yesterday Clause 58 read:

"By entering the Competition you grant to OS (and Ordnance Survey Leisure Limited) a non- exclusive, royalty free, worldwide, perpetual licence to ... (b) include your photo in our library of images and use it commercially, including but without limitation in our calendars, electonic wallpaper, on the OS website, and in promotional materials, (and sub-licence its use to others for their personal use accordingly). Subject to Clause 59 below, we will not always publish your name and you waive your moral rights in this respect."

Effectively this would allow them to take any photo that was entered and do whatever they liked with it, including selling it on, and without any obligation to credit the photographer.

Today, I decided I'd do a blog entry about it and went back to the competition website. And look:

Clause 58 now says “By entering the Competition you grant to OS (and Ordnance Survey Leisure Limited), a non- exclusive, royalty free, worldwide, perpetual licence to publish your photo(s) on the OS Photofit website, our corporate website and social media websites (such as Facebook and Twitter), and otherwise use the photo, in connection with this Competition”. In other words, whether your photo ends up as one of the winners or not, they can make widespread use of it as long as it has some link to the competition.

And a new Clause 59 says “In the event that your photo is one of the Competition winners, you further grant to OS and Ordnance Survey Leisure Limited a non-exclusive, royalty free, worldwide and perpetual licence to publish the photo(s) on the cover of any of its paper maps, on the OS website, in promotional materials and otherwise use the photo in connection with the business of OS. If your photo is appearing on one of our map covers, we assume that you will want your name to appear on the map cover to indicate that you are the photographer/copyright owner and by entering the Competition you agree that we can do this."

I wouldn't say this is brilliant even now but it does seem like a significant concession, presumably in response to the very strong social media reaction.

Here's a photo that still won't be appearing on any OS map covers any time soon.

]]>

If you look through the list of current Nikon cameras, some things start to stand out. First, Nikon doesn’t automatically withdraw older models when an upgrade or replacement comes along. The Nikon UK website currently lists not only the D7100 but the D7000 and even the D90, which is arguably the direct precursor of the D7000. The D5300, D5200 and D5100 are all there, as are the D3300, D3200 and D3100. With the lower-end models in particular, the product cycle is now little more than 12 months, many of the upgrades from one model to the next are incremental at best, and buying a slightly older model can be one way to get a real bargain. (If you don’t need onboard WiFi, for example, there;’s not a lot to set the D5300 apart from the D5200, apart from £150 or so).

However, one model sits rather forlornly on its own; the D300s. This appeared back in 2009. The ‘s’ suffix seems to imply that it was itself a modest upgrade to the D300 rather than a totally new camera, but that’s a bit misleading. Nikon’s model-numbering policy is opaque at best, but I think it’s fair to say that the difference between, say the D3200 and D3300 is considerably less than between D300 and D300s.

The D300, for instance, could not shoot movies; the D300s could, even if its movie mode looks pretty basic alongside current models like the D750. The D300s also added a second card slot (definitely a must for pro use) and a faster maximum shooting rate. It retained most of the other features including a very high standard of ruggedness and weather-sealing. Its control layout and interface was also very much in line with professional expectations – there are no Scene or Effects modes, for instance, just the four key exposure modes; (P) Program, (A) Aperture-priority, (S) Shutter-priority, and (M) Manual. (For a comparison of the D300s with the D7100, see this article).

Just look at what else was in Nikon’s range at the time: D3 and D3x, D700, D90, D5000 and D3000. Every one of those models has been upgraded several times. I’ve already mentioned the other DX models. In the FX range, the D3 gave way to the D3s, then the D4 and D4s. The D700 was never upgraded, but we now have D810, D750, D610 and Df, so that we now have more models in the FX family than in DX.

All this activity, and yet the D300s soldiers on, more than five years after launch, albeit now with limited availability. You can still pick one up from Jessops, for example, for £879.

This raises, the question, of course – what is Nikon playing at here? They’ve never said that they won’t produce a new professional DX model (whatever it might be called – we’ll use the tag ‘D400’ from here on), but then again, neither have they ever said that they will. This has kept the rumour sites active for years.

I can’t read the minds of the decision-makers at Nikon, and I don’t have any other kind of insider access, but it does appear that part of Nikon’s strategy is to encourage high-end users, whether enthusiast or pro, to migrate to FX. The DX models don’t just compete with other APS-format DSLRs – which basically means Canon and Pentax – but with other formats, notably mirrorless or compact system cameras (CSCs). The full-frame marketplace may be smaller but it’s also a lot less crowded.

Still, the rumour mill seems to suggest there is substantial latent demand for a professional DX SLR. Nikon may have calculated that this actually represents a very small, but very vocal, group that won’t count for very much in terms of sales. I wonder – because it seems to me that I could definitely be a potential customer for a D400 – but there are some serious provisos.

As regular readers know, I spend a good deal of my time shooting well away from any road, mostly either on foot or on a mountain bike. Naturally, I’m interested in lightening the load on my back whenever possible, but as several previous posts have discussed, I don’t want to compromise on image quality or the ability to capture fast-moving action.

Shot on a D300s above Davos, Switzerland

Shot on a D300s above Davos, Switzerland

In fact, there isn’t necessarily a massive difference between DX and FX in terms of body-weight. I’m currently shooting with a D600 and a D7000, and there’s very little between them in size or weight. Of course the D810, which does have a more rugged spec and better spread of AF points than the D600, is a couple of hundred grams heavier – but what really makes the difference is when you are carrying several lenses.

To cover the larger sensor, lenses for FX cameras need to be larger and heavier than their DX equivalents. You can use DX lenses on an FX camera, but the image needs to be cropped; you can also use FX lenses on a DX body, but there’s a penalty in weight and bulk. And Nikon’s DX lens range is notably lacking in what we could call ‘pro’ lenses – primes, or zooms with a constant, fast, maximum aperture.

Now there are lenses from other makers (e.g. Sigma, Tokina, Tamron), which plug at least some of these gaps, but it might not be a smart move by Nikon to bring out a camera body which encourages users to buy other makers’ lenses.

From my own point of view, most of the lenses I have are full-frame. This is partly because I need to be able to use them with FX cameras; as well as my own D600, FX cameras pass through my hands regularly for Expanded Guide purposes. And even if I had bottomless funds (which I most definitely don’t), I couldn’t assemble two full outfits because there simply is no DX equivalent for some of the lenses I use, like my 70–200mm f/4 or 300m f/4.

Without at least a core range of professional DX lenses, the appeal of a professional DX body is strictly limited. At least to me, and I suspect that’s how many others will see it too. If it saves me 200g over a D810 but I’m still carrying the same lenses, the benefit is much less than if it enables me to carry a different set of lenses and save a kilo or more.

And I also suspect that it’s the cost of introducing such lenses, not that of developing a new camera body, which has deterred Nikon from launching a D400.

I don’t underestimate the cost of developing or tooling up a new camera body, but it’s clear that there is a high degree of modularity, so that the most recent camera, the D750, shares many features with other models in the range; the sensor is similar to that in the D610 while the autofocus module is similar to the D810. It also inherits its onboard WiFi from the D5200. There’s no technical reason why Nikon could not produce a D400 body fairly quickly. But producing the right lenses to give it full system backup would be a longer and more costly task.

In addition, for users who are really concerned about weight and bulk, a D400 would emerge into a much more competitive marketplace than the D300s did five years ago. Mirrorless cameras like the Olympus OM-D series, Fujifilm X-T1 and Sony A7 models all produce excellent image quality. I’ve looked long and hard at some of these, but none of them yet fully measure up to the focusing speed of a good DSLR. Still, this is another factor which chips away at the potential market for a D400.

And there’s another strand which is keeping the rumour mills busy – the prospect that Nikon is working on a mirrorless camera, possibly a full-frame model. This may be another reason why the D400 is on the back-burner, and may never come to the front..

Shot on a D300s above Davos, Switzerland

This is not going to be a detailed review of either camera. There’s dpreview for that – see their thoughts on the D810 and the D750. You can also get a view on their image quality from DxoMark. What follows is simply my personal impressions of both cameras, based on fairly short but intense periods shooting with them.

Image Quality

Quite simply, I have no complaints abut the image quality of either camera. The obvious difference is that the D810 has 50% more megapixels, but that’s of little practical benefit to me most of the time. It doesn’t produce visibly better results in any of my regular outlets, even a magazine double-page spread.

It’s perhaps worth saying that I used images from a range of cameras for my cycling photo exhibition, currently on view at Wheelbase at Staveley in Cumbria (if you want to see it, get there before the end of the year). The prints are 30 x 20 inches, which is pretty big by most standards. The cameras used range from 6 to 24 megapixels and, though you might, on very close inspection, be able to identify the ones from the 6mp camera (Nikon D70), I’d defy anyone to reliably distinguish between those from 12, 16 or 24mp cameras.

Catshaw Greave, Forest of Bowland

The D810 handles extended dynamic range superbly well (this is from a single RAW file) – but the D750 is darn near as good

For my work, and for the vast majority of what most photographers do, there’s only one possible advantage in 36 megapixels, and that’s the additional scope to crop images severely. I recognise this but it’s not massively important to me as I always try to frame images in-camera. I’m not doctrinaire about it and will crop when necessary but always prefer the final image to reflect what I saw in the viewfinder.

On the other hand, the difference between 36mp (D810) and 24mp (D750) is very apparent in the extra demands on memory card and hard disk capacity, and in slower processing when working with images in Lightroom. These negatives actually outweigh, for me, the occasional crop-ability benefits of the D810.

It’s also worth saying that the massive resolution of the D810/D810 is wasted unless it’s matched by excellent lenses and impeccable technique. And not all the photography I do allows me to set up a sturdy tripod for every single shot...

No time to set up a tripod here!

Three Peaks cyclo-cross, shooting for Outdoor Fitness magazine near the summit of Ingleborough (and I carried both cameras, a range of lenses, and a flashgun... they aren't THAT heavy!)

On every other measure of image quality, i.e. really important things like dynamic range, there’s little to choose between them and both are excellent.

Build and handling

There’s no doubt that the D810 has a slightly more rugged feel to it, and has a higher level of weather-sealing. This is significant, but when I need to shoot in really foul conditions I have a ThinkTank Hydrophobia ‘rain jacket’ which I’ll use anyway. And the D750 is hardly fragile – it compares well with the D600 and D7000 which I’ve used regularly in all sorts of conditions. The D7000 is four years old now and still going strong.

On the other hand the D750 is noticeably lighter and smaller – in fact, Df apart, it’s Nikon’s lightest full-frame DSLR to date. As a hiking and biking photographer this does count for quite a bit.

The other obvious difference between the two is that the D810 has a fixed screen while the D750’s folds out. I don’t normally use the screen for shooting stills and I don’t shoot a lot of video (though maybe I should do more...), so this is not a massive deal for me, but there are times, mostly when using a tripod, that the folding screen does have its advantages, such as when shooting at very low angles. On the other hand the screen seems more vulnerable to damage and it is just slightly fiddly to make sure it is fully stowed away before moving on. I’d say there are both pros and cons to the folding screen and I’m not sure yet which way the balance tips for me.

Folding screen on the D750

One other difference is that the D750 has dual SD card slots while the D810 has one SD and one Compact Flash, I know some people feel that CF cards are more professional in some way, but for me it’s just a pain having to deal with two different types. This is a definite plus point for the D750.

In most other respects there’s not too much difference between the two cameras. The control layout is all familiar Nikon stuff and I’ve experienced very few glitches either switching between the two or on going back to the D7000 or D600. When working with the D810 and D750 together I was able to shuffle pretty seamlessly between the two.

In use

When Nikon launched the D750 they made a lot of play about its speed. Its maximum continuous shooting speed is 6.5 fps, well ahead of the D810’s 5fps – itself an improvement on the D800. (For comparison, the D600 manages 5.5 and the D7000 6fps).

Against this, the D810 has higher buffer capacity so is able to shoot longer continuous bursts. personally I rarely shoot more than 6 or 8 frames in a burst so this is almost immaterial to me, but it might be of importance to some sports shooters. The extra speed of the D750 is of much greater value to me.

I’ve found the autofocus performance of both cameras to be excellent. I tested the D810 shooting high-speed cycle racing in Lancaster city centre and even as night drew on, so that the main light source was street-lighting, it didn’t miss a beat. The D750 also performed brilliantly when shooting the the 3 Peaks cyclo-cross race in heavily overcast conditions.

High speed, low light

The D810 performed superbly in these demanding lighting conditions

There is one important difference, however, in that the area covered by the autofocus points is wider in the D810, and this is something that does make a real difference to some of my work. (The D600’s AF point coverage is narrower again, which is one reason why I still use my D70000 quite a bit to shoot action). I noticed this recently when shooting at an indoor climbing wall as I often wanted to focus on a climber’s face or hand that was quite close to the corners of the frame and outwith the focus point coverage.

If there is one factor that would make me choose the D810 in preference to the D750, this would be it.

On balance

But that’s only one factor, and as you can see from the foregoing, there are quite a few reasons for me to prefer the D750. It’s lighter and more compact, it’s faster, the folding screen is occasionally useful, and it uses the same type of card for both slots. The smaller file size also speeds up my workflow on desk days.

Does that mean I’m rushing out to buy one? Not yet. It doesn’t really do anything that I can’t already do with my D600 and D7000. It does a few things slightly better, but on a finite budget I need to balance that against alternative spending options like new lenses...

And besides, I have a feeling (and judging by the rumour mill, I’m not alone) that Nikon is about to reveal something interesting in the DX department, though whether it’s a modest upgrade to the D7100, i.e. a D7200, or something more dramatic, perhaps even the long-awaited ‘pr0 DX’ replacement for the D300/D300s, remains to be seen.

Anyway, the D810 has gone back and I have managed just fine without it. The D750, too, will go back when I’ve finished dealing with editorial queries on the book, and I suspect I will miss it only slightly. I’m sure there’ll come a time, before too long, when I can convincingly say ‘I need a new camera’ rather than just ‘I want a new camera’, but I’m not there yet.

Which is not to say that the D750 and D810 aren’t excellent cameras. They are. If money were no object I might even have both.

Hoverfly

As you’d expect, the D810 is great at recording fine detail, like the lenses of the compound eyes...

Dalton Crags

...but the D750 also does an excellent job on finely detailed subjects. 24 megapixels is still a lot!

Fireworks and Pendolino, Lancaster

The D750 did a great job on this shoot too, capturing images with very little noise even on long exposures (this one is 57 seconds).

]]>

“That’s not a landscape photo.”

“Why not?”

“Because there’s a person in it.”

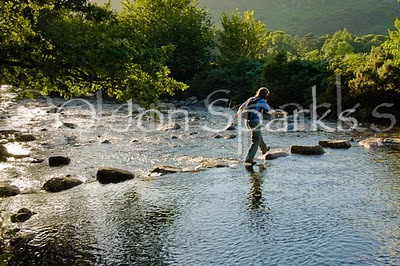

This is, almost verbatim, an exchange I had with a student on one of my courses a long time ago. Politely, of course, I begged to differ. Partly because I’m not that fussed about whether any particular photo is, or isn’t, a ‘Landscape’ (capital ‘L’ essential, I think) – and partly because I think that the human element often adds meaning to images. It can help to give the viewer a sense of connection or involvement with the landscape, and it often helps give a better sense of scale too.

For me, there are lots of situations where I want a figure in some of my shots, and I don’t always have anyone else at hand to act as a model. This means that the only option is to become my own model. If the figure is to be static, it isn’t terribly hard to do, but there are still a few things to think about.

So let’s look at Putting Yourself in the Picture (PYITP for short). First of all, you have to have some way of triggering the camera when you aren’t right behind it.

Trigger happy

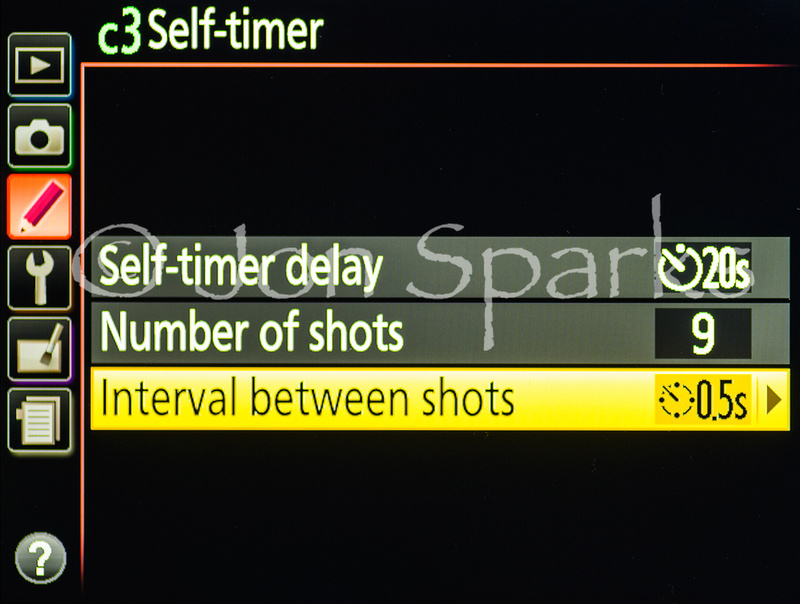

The most obvious of these is the self-timer. Most cameras have one of these, though in some cases you might have to ferret around in the menus to find it. This fires the shutter at a set interval after you press the button, giving you time to stroll, or possibly sprint, into the required position. Ten seconds seems to be a standard interval, though some cameras allow you to select longer or shorter times too. The Nikon SLRs which I use have a maximum delay of 20 secs, which allows a lot more flexibility, especially when you want to position yourself a significant distance from the camera.

Another possibility is to use a wireless remote control device. A few cameras even come with one in the box, but usually it’s a separate purchase, though not necessarily an expensive one. I’ve got a Nikon ML-L3, a simple little infrared unit which allows the camera to be triggered from a distance of up to 5 metres. List price is just under £20 and you can get it for less. It works with most Nikon SLRs as well as a number of Coolpix and Nikon 1 models. There are comparable products for most other makes.

That 5-metre range is the most obvious limitation – there are 3rd party units which have a much longer range, but at a higher price. The other concern when using such a device for PYITP is that you don’t necessarily want to appear to be obviously pointing something at the camera. My SLRs have a ‘delayed remote’ mode which means that the shutter trips 2 seconds after pressing the remote button – just long enough to conceal the device and rearrange myself into a more ‘natural’ pose.

The third, and most flexible option, is to use the interval timer. This allows me to set any delay up to 24 hours, and to shoot an almost unlimited number of images (certainly enough to fill up a memory card and drain the battery!) at intervals thereafter. This is way over the top for PYITP, but it does mean, for example, that if I want to be that tiny figure silhouetted on the edge of the crag I can set a suitable delay of 10 minutes, or whatever it takes. Setting the options takes a fraction longer than using the self-timer, but there are times when this level of flexibility makes it the only viable choice. Of course, not every camera has an interval timer – it’s missing from Nikon’s entry-level D3300 DSLR, for example.

In practice, the one that I use most often is the self-timer. On my Nikons (a D7000 and a D600) there’s also the option to fire a sequence of up to 9 shots, at intervals between 0.5 and 3 secs, For instance, if I set a 20 sec delay and 1 sec interval, the camera will take its first shot after 20 secs, the next at 21 secs (1 sec later) and so on up to 29 secs after first pressing the button.

Exactly how I use this depends on the situation and the type of action I’m trying to capture – we’ll look at one or two examples later. But the timing isn’t the only thing that needs to be thought about; for a start, there’s the where as well as the when.

Right time, right place

The ‘where’ aspect is all about the placement, size and visual impact of the figure in the frame. When you have someone else to act as ‘model’ you can judge this easily by eye and through the viewfinder. Unless you’ve worked out how to be in two places at once, you can’t do this when you’re on your own.

This aspect of PYITP can be either challenging or fun, depending on how you embrace it. You have to imagine – or, in a more ‘photographer-y’ word, visualise –where the figure fits into the overall image. Of course you can take a shot and check it on the camera back, but it can be a fairly lengthy process of trail and error unless you can short-cut it with some pre-visualisation.

Experience obviously helps, particularly in developing a sense of how large a figure will appear in the frame when they are at a particular point. Objects of comparable scale, such as walls, gates, signposts, shrubs, can be very useful reference points but they aren’t always there in open settings such as a beach or a mountain ridge. (In fact these are just the settings where a human figure in shot can be particularly powerful in terms of creating a sense of scale).

When you’re using a wide-angle lens, then even quite small shifts in position of the figure can make a big difference to its size and impact in the frame. With longer lenses, a shift of a metre or two may be much less crucial, but you’ll probably have to be farther from the camera to get into the shot at all.

Sometimes there will be obvious landmarks or reference points – scrambling along a mountain ridge, there may be an obvious crest or edge where you’ll be well outlined against the sky or against a distant backdrop. It nearly always pays to identify something, even if it’s just a particular tuft of grass, to aim for once you trip the timer and start scurrying off to get into shot.

When working out where to place yourself, think about the light too –, especially if it’s patchy (e.g. in a forest). One good way to tell if you’re fully illuminated when standing at a certain point is to look at your shadow – is it complete?

Dynamic element

When a static figure is all you need, it all seems relatively straightforward: set the timer, get into position, wait a few seconds (or until you hear the shutter click). Check image on camera-back and if satisfied, move on. When you want an element of action in the shot, it gets harder. In particular, timing becomes much more critical.

Undoubtedly, this is where it really helps to have a camera, like my Nikons (and many others) that can shoot multiple frames via self-timer or interval timer. It’s still hit and miss and it’s extremely hard to get that perfect ‘peak of the action’ shot, but you can certainly improve the odds in your favour.

Let’s look at a couple of real-life examples.

I’m currently working on a book of long (average c100km) road bike rides across the north of England. Wherever possible I’m doing these with someone else, and I’ll certainly take any opportunity offered by other riders randomly encountered en route – but I’ve had to do some of them solo and when doing them midweek there often haven’t been many other cyclists around, let alone on the stretches where I want a photo.

The first problem is that I’m travelling light (I did mention these were 100km rides, often hilly, didn’t I?) So I’m not carrying a tripod, and this means that I’m looking out for anything I can use as a place to set up the camera. In this case I’m on a lane above Lorton in the Lake District (a lovely sneaky was up to Whinlatter Pass, if you’re interested).

Another aspect I should mention is that I want riders in the photos, whether it’s me or someone else, to be travelling in the same direction as the ride is described. And I don’t want every shot to be a rear view. So the view in this shot isn’t what I saw in front of me as I was riding up the lane. In other words, you need eyes in the back of your head.

So, as the lane climbed and before it swung away to the right, I knew there was a good view behind and there was a continuous stone wall alongside which gave lots of potential places to set up the camera. I balanced the handlebar-bag which I use to carry the camera on top of the wall to give a bit of extra height and fiddled about with it until the overall framing looked right. I like the way the edge of the lane goes almost exactly into the corner of the frame, for example.

I then set the timer to 20 secs, number of frames to 9 and interval to 1 sec. I knew I needed the time to get a decent way down the road, turn round, clip back into the pedals and get under way again. Even so, on the first attempt I went a little too far and so was still quite small in the frame even for shot no 9. So I tried to adjust my pace a bit and the two shots here are nos 7 and 8 from the second attempt. As you can see, even at fairly moderate speed (it’s steeper than it looks), a cyclist can move a fair distance in a second.

I think my ideal would have been somewhere between the two shots. I’d really like the second shot if I was maybe half a meter further away – just far enough to get the whole of my shadow into shot. But there was no guarantee that I would do any better on a third attempt, and I needed to think about time, the distance remaining, and so on. I’d probably only spent 5 or 6 minutes at this location, but 5–6 minutes repeated 5 or 6 times adds half an hour to a trip. And that suggests that another aspect of PYITP is picking your locations carefully, so that each one counts.

Tech details: ISO 200); focal length 18mm on APS-C (27mm equivalent); aperture f/9 and shutter-speed 1/320 sec.

The second example also features me on a bike, but it’s a bit different because this was a magazine commission. There was a very specific requirement, to illustrate some of the major Yorkshire climbs which didn’t feature in this year’s Tour de France – but which will feature in the Hoy 100 sportive in September. (Which, by the way, I’ve just entered!).

I’d already spent some time on Park Rash and then moved on to Fleet Moss – Yorkshire’s highest road, climbing to 589 metres. It clouded over for a while so I actually rode down and back up the whole thing, partly to get a workout and partly by way of reconnaissance, but it was already pretty clear that this hairpin just below the top was a great spot to choose.

As I had the car with me I had no shortage of gear and could set the camera on a tripod exactly where I wanted – just as well, as there aren’t many alternative camera platforms hereabouts. Fortunately the band of cloud was moving over and I was getting some nice late afternoon light.

Again I set the timer to 20 secs but because the climb was steep I knew I might need extra time. I wanted to go back down to where it levels out slightly (the bit of road largely hidden by my torso in the picture). I decided that the thing to do was set the interval to the maximum 3 secs and, once I got to the key part and I could hear the shutter, slow right down. It’s not hard to do this as the gradient is around 20%!

Even so, I rode this section five times before I had a shot I was satisfied with – the light was great and, unlike the Lakes shot, my shadow is entirely in frame. The body language is appropriate, too. And obviously it worked, as the magazine used it across a double-page spread.